The United States has seen little progress at the national level in preventing new HIV cases over the past half decade, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“The number of people who acquire HIV each year is unacceptably high,” said Jonathan Mermin, MD, director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis and STD Prevention. “Ending this epidemic would be one of the greatest public health triumphs in our nation’s history.”

Some cities have made great strides toward ending the HIV epidemic. New York City, with a population of around 8.6 million, announced last month that new diagnoses fell below 2,000 for the first time since the peak of the epidemic. San Francisco, with a population about one tenth the size, has seen new diagnoses dip below 200. And in 2017, Seattle announced that it was among the first U.S. cities to achieve the UNAIDS targets: 90% of people living with HIV know their status, 90% of those diagnosed are on treatment and 90% of those on treatment have viral suppression.

But progress has been uneven, both when comparing cities and regions and when looking across demographic groups within cities. Black and Latino people, young people, transgender individuals, those living in rural areas, people with substance use issues and those experiencing homelessness are less likely to know they have HIV and less likely to have the virus under control.

Source: CDC Vital Signs, December 2019Courtesy of CDC

The CDC’s latest Vital Signs report (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, December 6, 2019) looks at progress toward ending HIV transmission.

The authors analyzed data reported to the National HIV Surveillance System through June 2019 from 50 states and Washington, DC, for people age 13 or older with diagnosed HIV. Modeling was done to estimate the annual number of new HIV infections between 2013 and 2017, the total number of people living with HIV (diagnosed and undiagnosed) at the end of 2017 and the percentage of people with HIV who had ever received a diagnosis. Data from 41 states and Washington, DC, all of which had complete laboratory reporting of viral load test results, were used to determine viral suppression rates. Information on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use came from the IQVIA Real World Data–Longitudinal Prescriptions database.

The report shows that the estimated number of people contracting HIV stalled at around 38,000 per year during this period, falling only slightly from 38,500 new infections in 2013 to 37,500 in 2017.

“In this case, stability is not good,” Eugene McCray, MD, director of the CDC’s division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, said during a December 3 media telebriefing about the report. “A previous analysis found that the number of new HIV infections declined from 2008 to 2013. We estimate that the decline has stopped.”

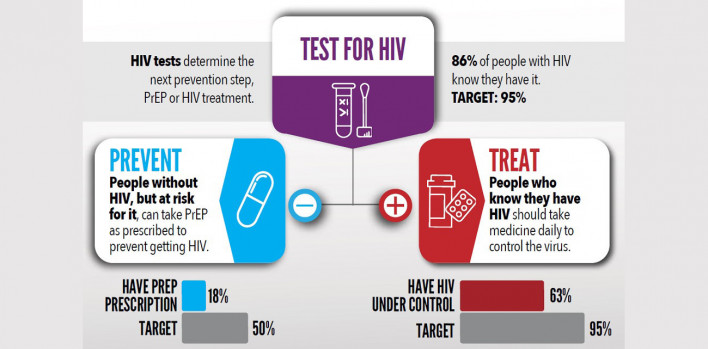

Around 154,000 (14%) of the estimated 1.2 million people living with HIV in 2017 have not been tested and do not know their status, according to the report. This rose to 45% undiagnosed among those younger than 25. Nevada had the highest proportion of undiagnosed people, at just over 20%, while New Jersey had the lowest, at about 6%.

Among the approximately 845,000 people with diagnosed HIV, 318,000 (37%) had not achieved sustained viral suppression. But some groups had substantially higher proportions living with uncontrolled HIV, including people under 25 (43%), African Americans (43%) and men who inject drugs (48%). South Dakota had the highest proportion of people with unsuppressed virus (53%), while Iowa had the lowest (20%).

Overall, 61% of people who started treatment achieved viral suppression within six months, but in 12 jurisdictions this proportion fell below 59%.

The government’s goal for both testing and viral suppression is 95%.

About 219,7000 (18%) of the estimated 1.2 million people who could benefit from PrEP had received a prescription for Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) for HIV prevention in 2018—far short of the government’s goal of 50%. The report authors acknowledged that this is likely an underestimate, as the data come from retail pharmacies and do not include, for example, closed health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente, or military health plans.

Men were three times more likely than women to be using PrEP (21% versus 7%). Among young people, just 11% were prescribed PrEP. About 42% of eligible white people, 11% of Latinos and 6% of Black people were on PrEP. These figures represent an improvement over CDC figures presented in 2018 that showed that just 14% of whites, 3% of Latinos and 1% of Blacks were using PrEP.

“There’s been a rapid increase in the number of people taking PrEP over the past three years,” McCray said. “But there’s no doubt that PrEP uptake is too low, and we’re working hard to increase access to PrEP, especially among gay and bisexual men, women, young people, African-Americans and Latinos.”

Source: CDC Vital Signs, December 2019Courtesy of CDC

Cities that have made progress toward ending the epidemic credit efforts to get more people tested, to get those diagnosed on treatment more rapidly and to make PrEP more widely available.

“Our nation’s public health community and all of us are ready to end the HIV epidemic. The science is there—we have the tools,” Jay Butler, MD, the CDC’s deputy director for infectious diseases, said during the telebriefing

“There’s a critical need to fully engage the community to include new voices and build capacity at the community level—that is, by the community and for the community,” Butler continued. “To be successful, we must also address social determinants of health. Too many Americans, including those with HIV or at risk of HIV, are facing serious issues that impact health and well-being, including homelessness, addiction and unaddressed mental health issues.”

Ready, Set, PrEP

To help address this shortfall, the Department of Health and Human Services recently announced a new program—dubbed Ready, Set, PrEP—to provide the prevention pill at no cost to those unable to pay for it.

The program will provide free PrEP for eligible individuals who are uninsured or do not have prescription drug coverage. However, depending on their income, they may still have to foot part of the bill for the recommended regular clinic visits and lab work to screen for sexually transmitted infections and monitor kidney function.

The two combination pills approved for HIV prevention, Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) and Descovy (tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine), cost around $1,600 per month. Gilead Sciences offers a patient assistance program for low-income individuals and co-pay cards to reduce out-of-pocket expenses for those with insurance, but many people continue to face financial and other barriers.

The program is a component of the government’s “Ending the HIV Epidemic” initiative, which President Donald Trump announced during this year’s State of the Union address. The initiative aims to reduce new HIV infections by 75% in five years and by 90% in 10 years.

“Ready, Set, PrEP is a historic expansion of access to HIV prevention medication and a major step forward in President Trump’s plan to end the HIV epidemic in America,” Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar said in a statement. “Thanks to Ready, Set, PrEP, thousands of Americans who are at risk for HIV will now be able to protect themselves and their communities."

Click here to read the Vital Signs report.

1 Comment

1 Comment